Origins of punctuation

Image: Wikimedia Commons

Regular readers will know that we’ve written a range of articles in the past about the purpose of different punctuation marks and how to use them in your writing. This time, I want to talk about the origins of punctuation itself.

You might think that humans invented punctuation at the same time as they invented written language. Not so. Early texts in many different cultures were simply a string of letters, without even spaces between words.

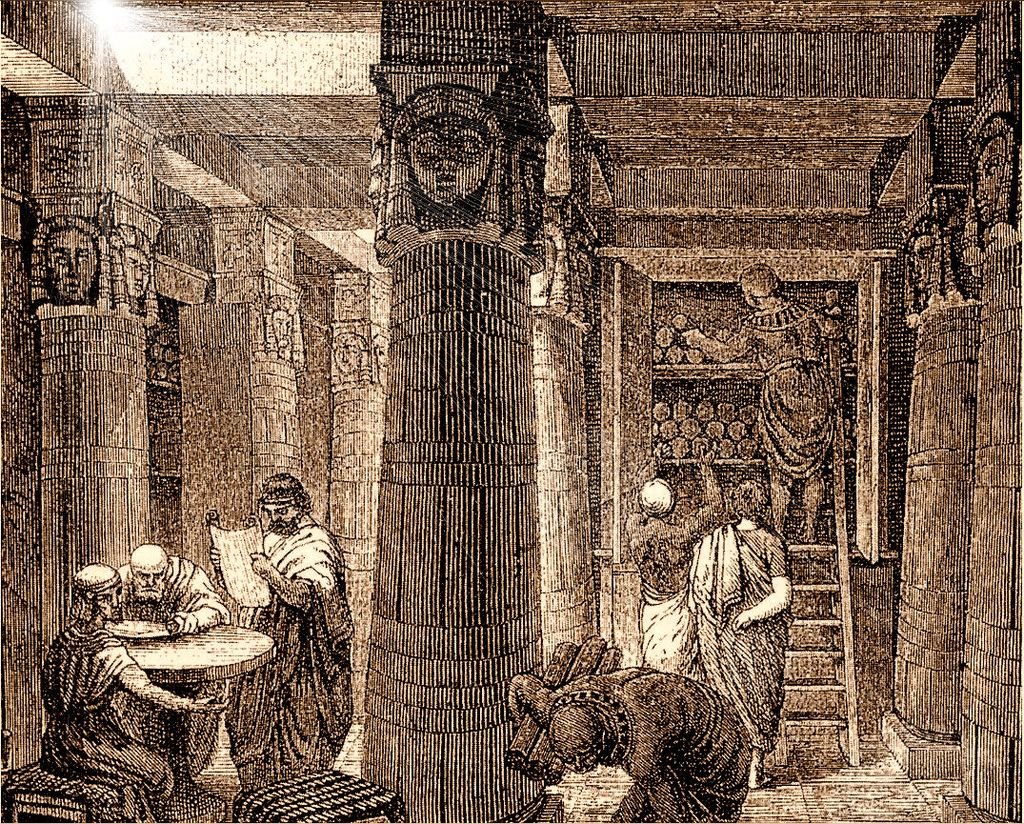

Keith Houston, author of Shady characters: the secret life of punctuation, symbols, and other typographical marks, says that punctuation marks evolved as a form of annotation used by Aristophanes, a Greek scholar at the Great Library of Alexandria around 200 BCE, to reflect the natural pauses used when reading. He would markup texts with symbols that represented the length of the pause – either a komma, kolon or periodos.

It’s generally accepted that there are 16 punctuation marks in English grammar: the full stop (or ‘period’ in North American English), question mark, exclamation mark, comma, semicolon, colon, em dash, en dash, hyphen, parenthesis, bracket, brace, apostrophe, double quotation mark, single quotation mark and ellipsis.

However, not all sources agree on this number, particularly when it comes to what is a punctuation mark and what is a symbol. Of the 16, the em dash is probably most under threat, with the Australian Government Style manual recommending against their use except ‘to show a sudden interruption in quotations and reported speech’ by inserting 2 em dashes in a row.

Sometimes punctuation is a matter of personal preference, while other times the meaning of a sentence can change completely depending on the presence or otherwise of these subtle linguistic signposts. Professional editors – not a group that is normally thought of as being particularly militant – can get very stroppy about the correct placement of a comma.

The Plain English Foundation estimates that about 80% of punctuation choices are set by clear grammatical rules. That might not be comforting for people who like boundaries and structure to know that the other 20% of the time they must rely on their own judgement.

The best test of whether you have applied the punctuation symbols correctly in your writing is by putting them to use. Read what you have written, either out loud or in your mind, applying the pauses and emphasis as indicated by those little squiggles. If it doesn’t sound like what you are trying to say, you probably need to review your punctuation choices.